From Grief to Grace

October 13, 2020 – by Era Martin

Loss

I stared at the video screen on the seatback in front of me. Emotions threatened to erupt – grief, despair, powerlessness. Tears yearned to flow, swelling inside me so rapidly that I was afraid I’d burst. But surrounded by airplane passengers in economy class wasn’t the place to explode.

Korean flight attendants rushed through the narrow aisles preparing for takeoff. One noticed my face contorted by emotion. She halted in front of me and asked in a concerned, gentle manner, “What’s the matter?”

“I thought we’d fly across Honshu – not curve northeast over Hokkaido. I lived many years in Japan, and my best teacher – ever – lived in Hiroshima. I wanted to fly overhead,” I said, while pointing at the airplane route on the screen.

Spurts of phrases spilled out of my mouth, yet I maintained a soft, emotionally-mature tone so expected in many parts of Asia. Overwhelmed, my ears were deaf to whatever she might’ve said before moving on with her other duties. The ability to state my distress and desire at all surprised me.

If I thought my emotions wouldn’t overflow, I would’ve let her also know that very day one year prior was when my late teacher, Takenori Sera, had died from pancreatic cancer. I believed, though, that she did grasp the gravity of my deep respect and compassion without a spoken word.

Our seatbelts fastened, the plane departed Incheon International Airport for Los Angeles. With closed eyes for a time, I began observing my breath to gain some peace within. A few thoughts surfaced like bubbles in water. My mind’s geographical map was incorrect, and I had not considered the fact planes fly on geodesic paths – not straight across wide expanses like the Pacific Ocean. Then I figured if I had looked at a map and determined probable flying routes ahead of time, I wouldn’t have had any expectations of flying over Honshu.

Our route’s progress remained lit on the screen when I eventually opened them. To my sheer amazement, we were approaching Honshu Island. Was this a dream? In fact, the map showed we flew southeast near Pusan, crossed over the Sea of Japan to align with Hiroshima! What a miracle. Had the gracious flight attendant understood the value I placed on my great teacher, and honored me by asking the pilots if we could go out of our way to pass over my desired location without losing time?

Now a few tears quietly trickled down my cheeks with joy and gratitude. While over Hiroshima, they flowed. While flying straight across Honshu, a dream state continued. While over Tokyo, I extended my gratitude to my spiritual teacher’s teacher, Tsuyoshi Nara, who also played a critical role in my life. He had died one and a half years prior to Master Sera.

I closed my eyes again, and a clear vision of both of these two teachers appeared in bluish-gray, Shinto ritual clothing. I recalled our special relationships.

This trip marked the end of my year as a director for foreign teachers at five high schools in northern China and teaching at one in Xinxiang, Henan. This experience was an important step in my grieving process for my teachers.

I wrote a lengthy, sincere thank you letter to the airline’s staff. Included was a sentence about why that day was so precious to me. The company wrote back to say it was forwarded to the crew. This brought the flight event full circle. I encountered heartfelt satisfaction.

Beyond my teachers’ deaths and this incident, I have encountered the passing away of loved ones time and again throughout my life. Some of these were family losses. As a young child, for example, the death of my maternal grandfather was painful in itself, yet snowballed into tremendous loss. My grandparent’s southwest Michigan farm was sold where I cherished romping through the grape vineyard and peach orchard, eating apples high in a maple tree, playing with barn cats, riding my horse, and observing Nature.

All of this vanished.

Other close relatives passed, as did beloved pet cats and dogs – due to sickness, old age, or sudden accidents. Unexpected deaths were the most difficult. There wasn’t time to process their upcoming deaths, or to say what needed to be said and share special moments during final, precious days together.

Some deaths affected whole communities. With the onslaught of the AIDS pandemic in my late twenties, several of my San Francisco Bay Area friends became ill and succumbed – especially during those early days of uncertainty and the scrambling for answers. My feet didn’t feel like they were on solid ground. Societal shifts were painful, with feelings of isolation made more acute because numerous medical workers feared the unknown disease and so many common folks shunned homosexuals, as they did drug addicts. My heart ached as I visited ailing friends regularly and offered loving support as their community crumbled.

Sometimes the losses are even wider.

Now our world faces the COVID-19 pandemic. It brings other forms of personal, familial, and societal changes, along with new states of isolation. I recognize these shifts as “metaphorical deaths”. They, too, require grieving. Gatherings of family and friends, jobs, finances, and lifestyle habits encompass the scope of loss amid this calamity. Visiting a loved one in their final hours if in a hospital or nursing home isn’t even possible.

With these radical changes, most everyone seems to be experiencing some aspects of culture shock which typically occurs when adapting to a different culture in the world. This is because our habitual ways to organize, perceive, and do things suddenly change. Expectations aren’t met. And with such a large, global population of people affected by this virus, death is knocking at our door. I notice not only me, but others as well became supersensitive, with our personalities glaring in a raw manner – like when care giving for someone nearing death. Truths become stark naked.

Other forms of metaphorical deaths take a toll as well. The loss of close relationships, divorce, and moving from one place to another are a few examples of other emotional ones. And releases of unhealthy, psychological patterns that lingered over long periods of time also cause grief. Efforts to consciously process and finally rid something undesirable within seems like cause for celebration. Well it is, after recovering from the initial loss.

Even amid my pain of Masters Sera and Nara’s deaths, they provided tangible insights to collect a lifetime of lessons together. I came to understand my loss of them and obtain a way to mourn past, present, and future losses.

Transitions

Maybe learning to grieve takes most of us a lifetime. It certainly is an ongoing process for me. I recall distinct moments when a little piece of the puzzle of life and death seemed to fall into place.

I remember wandering the streets of Benares, India many years ago. Amid intense heat and the bustle of crowded, vibrant folks going about their daily lives, feeble, elderly Hindus slump over or recline in and around centuries-old, monolithic buildings, and elongated, concrete steps leading down to the holy Ganges River. They await their inevitable death in this most sacred location for an auspicious send off into the Heavens. The faithful in the late autumn of their lives long to be here for their final days.

While women in bright-colored saris bathe and wash clothes in the Ganges, men in Western, long pants and shirts or white loin cloths dip into these sacred waters to bathe as well. The Ganges River is also known for healing the ill by submerging one’s body into it. Funeral pyres burn yards away with the putrid smell of burning hair prior to the blessed ashes swooning into these mighty waters.

This interweaving of life and death before my very eyes was profoundly moving. I started to embrace this natural occurrence over several days, realizing these opposites of life and death on this material yin and yang plane are spiritually one. And while death refers to physical inactivity, life symbolizes vivaciousness. Death has a conceptual way of making me feel more alive with deeper clarity.

The frail awaiting death in Benares made me question how much emotional and spiritual completion is needed to allow oneself to take a final breath, especially when the physical body is ready to release itself. Witnessing this influenced my perspective later when I volunteered with a hospice organization in California.

In my teen years, I had enjoyed volunteering at senior homes helping with day activities and holiday-time singing events. So when the opportunity of hospice work was available, I took training and was assigned to an Alzheimer’s patient in his final stages. I was with the family for two hours a week over a period of several months.

Arriving at the house, I entered a creamy-toned, modest bedroom and saw my client lying in a bed for the first time, not eating or drinking, with eyes closed. Everyone knew he was waiting. His wife said he had been in this state for four or five days.

With his daughter and grandson on bended knees on either side of his single bed, along with a calm, observant hospice nurse seated in the corner, I held his hand for awhile. Then I placed my lips close to his left ear, softly and slowly saying, “You’ve been a wonderful husband, a great father, and an amazing grandfather. You provided so well for everyone. Your wife, daughter, and grandson all love you very much. They know you love them very much as well.”

After several silent minutes, now with his daughter and grandson each holding one of his hands, the hospice nurse noticed he took his last breath.

Maybe he was holding onto life because of words unspoken. The need to express love. The desired wish for completion.

With this loss came the desire for his family and others close to them to comfort each other in days ahead. This shared support – especially with ones who grieve the same loss – undoubtedly nourishes each other. And after about a year passed, a local grieving group was of additional help for them.

When our society-at-large is affected with the likes of AIDS and COVID-19, community and national projects connect people in broader and more powerful ways. The NAMES Project for AIDS victims was incredibly comforting for me and an intimate group of friends through the sharing of palpable feelings and memories, while designing and sewing a memorializing, three-by-six-foot quilt for our loved one.

Folks across the US participated as a wholehearted collective. A vast population of AIDS patients, their families, friends, and other loved ones felt isolation diminish. The collective and communities in our nation grew stronger. The finished folk art project, once sewn together for display in Washington, D.C., weighed around 52 tons and bursting with affection. A sense of completion with this venture and the opportunity to allow precious memories to linger for me became tangible through the book The Quilt: Stories from the NAMES Project, full of gathered photos, vignettes, and the evolution of this beloved project from its conception.

For COVID-19 and its worldwide implications, I reflect on my approaches to culture shock learned while living and traveling abroad. This is because lifestyle changes are typically radical, and a means to adjust and adapt is vital – for me, those I interact with on a daily basis, and society as a whole. First of all, I start with patience, acceptance of myself, and an understanding the process is ongoing to the degrees I can. Becoming a saint isn’t easy!

I remind myself to create and carry out constructive mental and physical activities; determine simple, attainable goals; keep in touch with loved ones; enjoy a hobby. Allowing myself to feel sad and acknowledge sorrow is healthy; yet focusing on my confidence and strength to move through transitions. I make efforts to be more humorous; grow more open minded; maintain positive regards and respect toward others. Having a defined, secure feeling about myself allows me to feel neither squandered nor forceful in my relationships with others.

These are many ways I learned to process culture shock and pandemics in my daily life. Undoubtedly, it’s all an ongoing process and gradual achievements bring sprinkles of peace and joy. Amid this, I’ve come to realize ample rest, meditation, and contemplation are as essential as breathing, eating, and sleeping.

Through ever growing faith and love in the Divine Source, I trust in the perfection of the sacred design. In this, I grow in wholeness and peace. I am comforted by the sacred plan – particularly when a child or someone who seems to be “too young” to die departs and moves on in accordance to the Divine blueprint. The deceased have completed their life lessons and mission here, regardless of age. And those left behind continue with theirs, along with exceptional opportunities to grow closer to the Divine due to loss.

I learned the depths of darkness on one side can swing to expansive light on the other like a pendulum. The degree of motion one way can swing just as far in the other direction. As the natural, human feeling of anger recedes amid grief, the same degree of openness is available to move toward the other side. With increasing patience, gentleness, and meditation or prayer, movement from the darkness gains speed toward the light.

Through clarity and a sense of soulful beauty within, and an expression of gratitude toward the Divine Source, the creation of the best possible outcome presents itself. The result for me has been beyond my imagination.

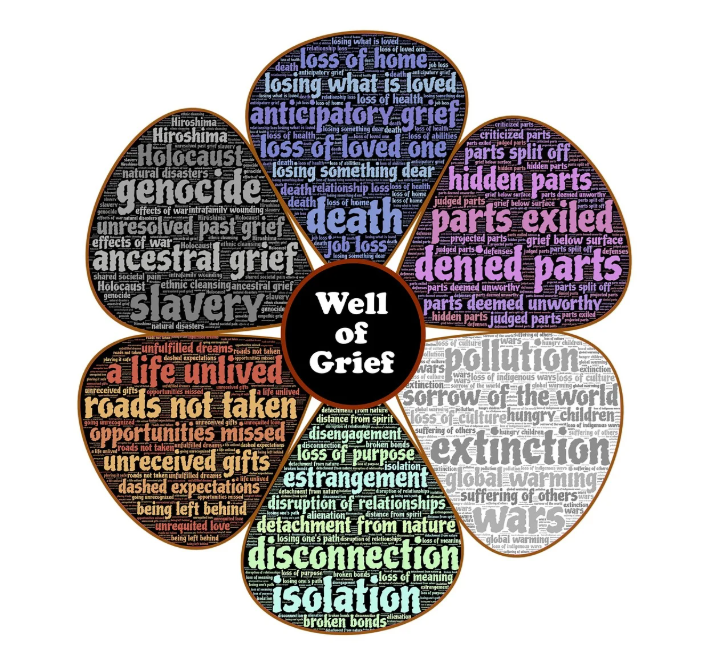

I also experienced a greater opportunity to clear the way further into the light and beyond due to past losses. My conscious and unconscious grief triggers to the forefront when a new death presents itself. The new grief is joined by lingering sorrow. They intertwine, and I offer them an opportunity to dance in solemnity amid my heart’s love and the inexhaustible support of the Divine.

Residue is cleansed away as purity flows in. An expression of gratitude for this natural process in the form of contemplation or prayer is potent. Gratitude, as an expression of love toward the Divine Source, creates a profound circulation between me and the All Compassionate Source. This is also when I apologize sincerely for my misgivings as well. I discovered these facets tap into the Source’s Eternal fountain of purity, love, and compassion.

Also while processing grief, I turn to Nature in stillness and silence. This profound power comforts me. I learned this precious tool from Master Sera.

The grace of blossoming flowers softens my rough, hard edges of bereavement. The patience of trees frees me to process sorrow with no time limit of days or years. Withering flowers and fallen trees express to me the natural cycle’s final stage all living beings encounter. This helps me accept loss, which in turn, offers inner peace.

I observe the four great Elements separately, namely Earth, Water, Fire, and Air, according to how Master Sera explained. I consider intuitively what insights Nature expresses about Them concretely and conceptually for me. With each observation, I intuit how they might relate to humans. Reflections and discoveries often relate to grief when it is so palpable. I keep in mind a vast array of possible observations exists, and their symbolisms are just as myriad.

A few of my Earth examples have already been presented. Even more, though, the cycle of seasons reminds me of the one constant – change. No season lasts forever. Everything and everybody perishes. Besides this helping me to gain acceptance and peace, I acknowledge perishing circles back to renewal, birth, and rebirth.

Water is fluid. This connotes to me the need to be adaptable and open to transformations. And rivers are clear and healthy when they have a moving current. So I need “circulation” to allow my heavy grief the opportunity to be fluid and adjust over time toward lightness. I also pray for clarity to gain further insights to assist in my grieving process.

Fire, firstly, is hot. This refers to a warm, loving heart. Secondly, fire is also active. With these two observations, I allow myself to feel the flow of love between the deceased and me.

Air is invisible; however it’s felt when the wind blows. The Divine Source is invisible. Yet, our spiritual experiences reflect the power, glory, compassion, and love of this Divine Source that exists. And when a breeze seems to come out of nowhere on a calm day, I consider the spirit of our loved one who physically passed away might be saying hello.

I realized the Elements depart from every physical body around the time of physical death. To observe, learn, and accept the Laws of Nature set forth from the beginning of time by the Eternal Source is a blessing. This, in turn, strengthens me to face loss with courage.

These are ways in which I learned to process grief in response to losses large and small.

Methods

The following five methods offer me solace when greater faith, insight, and empowerment become ever more critical amid my losses. They offer transitions from grief to grace:

One: In quietude, I do three things – preferably outside amid the natural world and definitely not where chemical fertilizers are used. Unnatural shapes and sizes of plants and flowers present an abstract perception of Nature and humanity, leaving our mind disorientated and unsettled.

I start by observing calm and beautiful qualities of Nature. Secondly, I apply intuition to notice one or two qualities or patterns of Her essence. Thirdly, I consider the symbolism of a given pattern or two related to humankind.

I allow internal shifts in my mind, heart, and spirit to happen without effort, and even devoid of any analysis. I permit lightness to be felt, sweeping away the heaviness of grief, and allow a sense of gratitude to arise. Maybe a feeling of comfort as though held by Mother Nature Herself drifts into awareness, or other heartfelt feelings arise. I just let it be.

Another way I obtain benefits from Nature is by observing Earth, Water, Fire, and Air separately. I decide to spend a day, a week, or a month, for instance, viewing and analyzing one given Element at a time. When an Element seems exhausted of stimulating observation, I move on to another.

Whether observing Nature as a whole or a specific Element, jotting down notes or keeping a journal of observations, analysis, and benefits gained provides later reflection.

Two: I welcome transformations when I allow sorrow to flow. My attempts to fight or control it are futile. It fights back. It does what it wants – sometimes with a vengeance. Moving towards acceptance of grief, of the Divine plan, and the natural intermingling of life and death helps me to soften my reality with grace.

I obtain relief by writing in a journal or by visiting a special place previously enjoyed with the person now absent. And when a loved one died in a difficult or brutal manner, I remind myself the fatal experience happened once for them – not numerous times like in my thoughts in the way a broken record plays.

Three: Connecting with others helps support me as a social creature – those who share in the same loss, those who are dear to me, and eventually those in grief groups, and community or national projects.

Since the NAMES Project, refuge for grievers was found in other AIDS quilt projects around the world and to remember victims afflicted by Breast cancer, Huntington’s disease, and Congenital Heart disease, for instance. Several 9-11 memorial quilt projects, the K.I.A. Memorial Quilt for military personnel killed in the Iraq War, and numerous other quilt projects followed as well.

Four: Both physical and metaphorical deaths invite me to set simple, attainable goals. Maybe that means the accomplishment of taking a shower or drinking a cup of tea in the morning. I then acknowledge my accomplishments with satisfaction when grief hits hard. When possible, a bit of structured time is added for a little activity.

With time, dashes of humor and perceiving step-by-step in new, open-minded ways are added to my mix. Defining a secure feeling of self, gaining more positivity, and maintaining respectful regards toward others help stabilize me through harmony with myself, others, and my environment.

Five: I remember that in my darkest moments, I have the opportunity to seize the richness of my own nature. I am stronger, and more adaptable and insightful than I might otherwise ever imagine. In a natural way, light seeps through cracks in the darkness. I gain speed toward the light through meditation, prayer, gratitude, and atonement.

A cage door opens. Once again, life beckons.

Publication history:

• First published October 13, 2020 by AMA Publication in a women’s anthology titled VISIONARY: The Future Belongs to Those Who Can See in the Dark. Obtained #1 Bestseller on Amazon in the US, UK, Netherlands, France, Australia, and Canada.

• Updated May 15, 2025 with image.